The Seduction of Black America: How Consumerism Became a Double-Edged Sword

- Admin

- Feb 12, 2025

- 4 min read

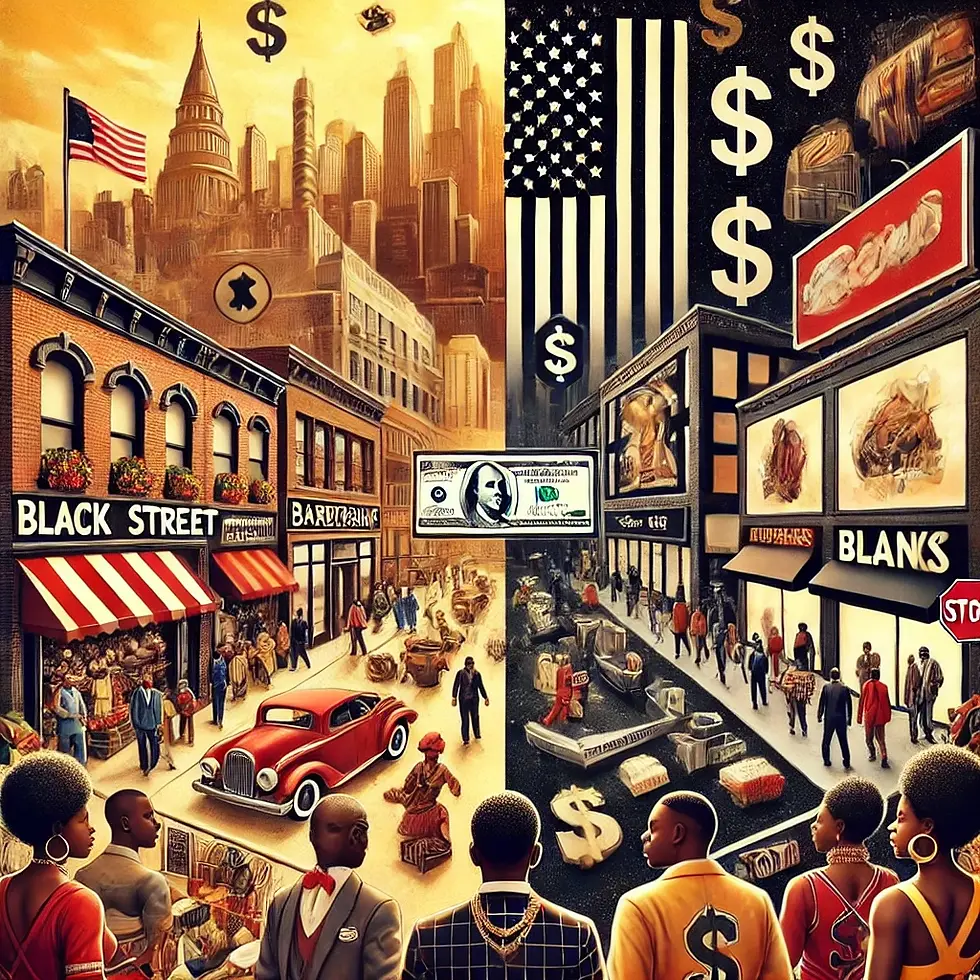

The American Dream has long been sold as a promise of prosperity, success, and financial security, with consumerism positioned as the ultimate proof of having "made it." For Black Americans, whose ancestors were once considered property rather than owners, the ability to acquire goods, homes, cars, and luxury items has been deeply intertwined with notions of freedom and progress. However, the seductive pull of American consumerism has created a paradox: while economic power should be a pathway to collective uplift, the perpetual cycle of spending has, in many ways, hindered long-term financial independence.

The Historical Context: From Exclusion to Inclusion

In the early 20th century, Black Americans were largely excluded from mainstream economic participation. Redlining, segregation, and discriminatory lending practices made wealth accumulation difficult. Yet, Black communities developed their own thriving economies—business districts like Tulsa’s Black Wall Street, Durham’s Hayti, and Chicago’s Bronzeville were testaments to Black self-sufficiency. In The Souls of Black Folk, W.E.B. Du Bois observed, "To be a poor man is hard, but to be a poor race in a land of dollars is the very bottom of hardships."

During the Great Migration (1916-1970), millions of Black Americans relocated from the South to urban centers in the North and West for better economic opportunities. This movement contributed to the growth of Black business districts, cultural institutions, and political activism. Despite these strides, economic disparities persisted as Black workers were often relegated to low-wage labor and denied access to wealth-building tools like homeownership and capital investment. Khalil Gibran Muhammad, in The Condemnation of Blackness, highlights how "African Americans were criminalized not just through the justice system but through economic policies that reinforced exclusion."

The Civil Rights Movement of the 1950s and 1960s brought about greater access to public accommodations and economic opportunities. Landmark legislation such as the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Fair Housing Act of 1968 sought to dismantle structural barriers. However, desegregation also had unintended economic consequences—many Black-owned businesses struggled to compete with larger, white-owned establishments that now had Black customers. Instead of reinforcing Black businesses and financial institutions, money increasingly flowed out of the community into white-owned corporations, many of which had previously barred Black patronage. Robin D.G. Kelley, in Freedom Dreams, notes, "Integration was both a victory and a defeat—it opened doors but also weakened the economic structures of self-sufficiency that Black communities had long relied upon."

The 1970s and 1980s saw the emergence of affirmative action policies and more excellent Black representation in corporate America. Yet, economic disparities remained, exacerbated by factors such as mass incarceration, deindustrialization, and a lack of generational wealth transfer. By the late 20th century, consumer marketing had become a dominant force, with corporations targeting Black consumers as a lucrative demographic, further embedding the idea that financial success was measured by material consumption rather than long-term wealth-building.

The Illusion of Economic Empowerment

By the 1980s and 1990s, as hip-hop culture gained mainstream traction, it became an influential vehicle for promoting luxury consumerism. Black success was often measured by visible markers of wealth—designer clothing, expensive cars, jewelry, and high-end real estate. Marketing campaigns targeted Black consumers with aspirational messaging, reinforcing that spending was synonymous with status. This was particularly evident in industries like sports, entertainment, and fashion, where Black celebrities became brand ambassadors for companies that did not invest in Black communities.

Despite these displays of affluence, Black wealth accumulation has remained disproportionately low. A 2021 report from the Brookings Institution found that the median wealth of Black families was just $24,100 compared to $188,200 for white families. This staggering gap highlights the limitations of consumer-driven success. While individual Black celebrities and entrepreneurs may amass great wealth, systemic barriers such as wage disparities, predatory lending, and a lack of generational wealth continue to hinder broader economic mobility.

Redefining Success: From Spending to Ownership

To reclaim economic power, Black America must move beyond the illusion of wealth through consumerism and refocus on ownership and financial literacy. Homeownership, investments, and entrepreneurship remain the most effective tools for economic empowerment. Supporting Black-owned businesses, banking with Black financial institutions, and prioritizing asset accumulation over conspicuous consumption can create sustainable economic growth within the community.

Additionally, education plays a crucial role. Schools and community organizations must emphasize financial literacy, teaching young people the principles of saving, investing, and cooperative economics. Without this shift, the cycle of spending without wealth accumulation will continue to benefit corporations at the expense of Black economic independence.

Moving forward, the challenge is redefining success—not by what we spend, but by what we own and pass down to future generations. Black Americans must shift from measuring economic achievement through material possessions to a broader vision of prosperity, including asset ownership, wealth transfer, and community investment. True success should be reflected in financial stability, the ability to fund education for future generations, and a legacy of wealth that outlives the individual.

This shift requires a fundamental change in mindset. It means celebrating entrepreneurship over brand loyalty, prioritizing investments over instant gratification, and supporting institutions that reinvest in the community. Programs promoting cooperative economics, business ownership, and financial planning should be championed as markers of real success.

As history has shown, Black Americans have always been resilient and resourceful. The next phase of economic empowerment depends on moving beyond the short-term satisfaction of spending and embracing the long-term benefits of ownership and investment. The power of the Black dollar is undeniable—now, it must be harnessed to create generational wealth and lasting prosperity.

Sources

Brookings Institution. "Examining the Black-White Wealth Gap." 2021. https://www.brookings.edu/research/examining-the-black-white-wealth-gap/

Du Bois, W.E.B. The Souls of Black Folk. Chicago: A.C. McClurg & Co., 1903.

Graham, Lawrence Otis. Our Kind of People: Inside America’s Black Upper Class. HarperCollins, 1999.

Kelley, Robin D.G. Freedom Dreams: The Black Radical Imagination. Beacon Press, 2002.

Muhammad, Khalil Gibran. The Condemnation of Blackness: Race, Crime, and the Making of Modern Urban America. Harvard University Press, 2010.

Tate, Gayle T. Unknown Tongues: Black Women’s Political Activism in the Antebellum Era, 1830-1860. Michigan State University Press, 2003.

Toney, Michael B. Black Wall Street: From Riot to Renaissance in Tulsa’s Historic Greenwood District. University of Oklahoma Press, 2018.

.jpg)

Comments